Nutrient-Dense Food

The 2015-2020 Dietary Guidelines for Americans recommend choosing a variety of nutrient-dense foods, including fruits like cranberries, which contain essential vitamins and minerals, dietary fiber and other naturally occurring compounds that may have potential health benefits.

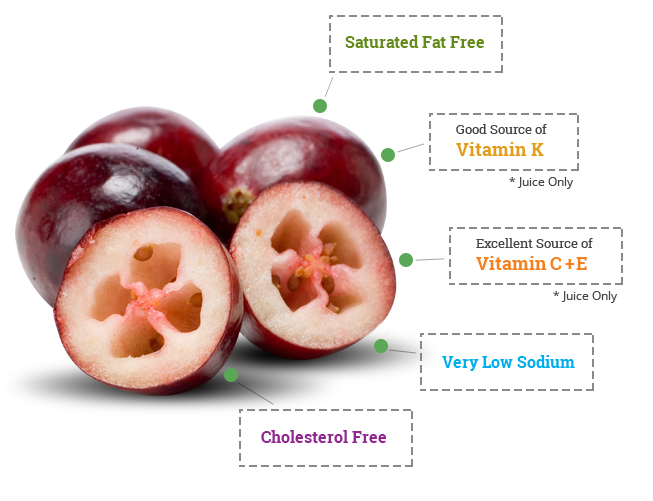

Low fat diets rich in fiber-containing grain products, fruits, and vegetables may reduce the risk of some types of cancer, a disease associated with many factors. While many factors affect heart disease, diets low in saturated fat and cholesterol may reduce the risk of this disease. Diets low in sodium may reduce the risk of high blood pressure, a disease associated with many factors. Cranberries are cholesterol and fat free, and very low in sodium.1

Antioxidants

Cranberry products contain polyphenol antioxidants.

Cranberry juice is an excellent source of antioxidant vitamins C and E. Some scientific evidence suggests that consumption of antioxidant vitamins may reduce the risk of certain forms of cancer. However, FDA has determined that this evidence is limited and not conclusive.

Tart Taste

Cranberry products are usually sweetened because, unlike other berries, cranberries are naturally low in sugar and high in acidity, making them especially tart. The Dietary Guidelines allow for a limited amount of added sugar to improve palatability and recommends less than 10 percent of calories per day be from added sugar. The total amount of sugar in dried cranberries is similar to that of other dried fruit.

Fruit, in all forms, provides vitamins and minerals as well as dietary fiber. By the nature of how it is made, dried fruit offers more concentrated nutrients than fresh fruit, allowing a smaller amount of dried fruit to provide similar benefits to a larger quantity of fresh fruit. Both the 2015-2020 Dietary Guidelines for Americans and MyPlate recognize ½ cup of dried fruit as equivalent to a 1 cup serving of fruit. These recommendations were made based on the nutrition contribution of this quantity of dried fruit, compared to fresh alternatives.

Research Supports Cranberries

More than 500 original research and review articles about cranberries have been published in peer-reviewed medical and nutrition journals. These include animal, laboratory and human clinical trials, as well as epidemiological studies. The current evidence, along with a comprehensive review of Cranberries and Their Bioactive Constituents in Human Health in the November 2013 issue of Advances in Nutrition, reveals that:

Cranberries are a source of dietary phenolic bioactives, including particularly flavan-3-ols, A-type proanthocyanidins, anthocyanins, benzoic acid and ursolic acid, and a unique profile of all six members of the anthocyanidin family.2 While the results of these studies show promising outcomes, these are not conclusive. Further human clinical trials are needed to fully understand the effects on humans.

Cranberries contain the flavanol, proanthocyanidin (PAC). The unusual A-type structure of the cranberry PAC appears to be responsible for the anti-adhesive properties that are not found in other PAC-containing fruits and vegetables.3

The majority of human studies have focused on cranberry’s beneficial effect on urinary tract health. Researchers continue to explore cranberry’s potential effects on oral health,4 cardiovascular disease,5 cancer,6-9 glycemic response,10-12 and infections such as Helicobacter pylori (H. pylori) bacteria, a cause of gastritis and peptic ulcer disease.13-15

REFERENCES:

- USDA National Nutrient Database for Standard Reference Legacy Release, April 2018

- Halvorsen, BL, Carlsen MH, Phillips KM, Bohn, SK, Holte K, Jacobs DR, and Blomho R. Content of redox-active compounds (ie, antioxidants) in foods consumed in the United States. Am J Clin Nutr. 2006;84:95-135.

- Howell AB, Reed J, Krueger C, Winterbottom R, Leahy M. A-type cranberry proanthocyanidins and uropathogenic bacterial anti-adhesion activity. Phytochemistry. 2005; 66 (18): 2281-2291.

- Feghali K, Feldman M, La VD, Santos J, Grenier D. Cranberry proanthocyanidins: natural weapons against periodontal diseases. J Agric Food Chem. 2012;60(23):5728–5735.

- McKay DL, Blumberg JB. Cranberries (Vaccinium macrocarpon) and cardiovascular disease risk factors. Nutr Rev. 2007;65:490-502.

- Neto CC. Cranberry and blueberry: evidence for protective effects against cancer and vascular diseases. Mol Nutr Food Res. 2007;51(6):652-64.

- Neto CC, Amoroso JW, Liberty AM. Anticancer activities of cranberry phytochemicals: an update. Mol Nutr Food Res. 2008;52(Suppl 1):S18-27.

- Roy S, Khanna S, Alessio HM, Vider J, Bagchi D, Bagchi M, Sen CK. Anti-angiogenic property of edible berries. Free Radic Res. 2002;36(9):1023-31.

- Babich H, Ickow IM, Weisburg JH, Zuckerbraun HL, Schuck AG. Cranberry juice extract, a mild prooxidant with cytotoxic properties independent of reactive oxygen species. Phytother Res. 2012;26(9):1358-1365.

- Blumberg JB, Terri A. Camesano TA, Cassidy A, Kris-Etherton P, Howell A, Manach C, Ostertag LM, Sies H, Skulas-Ray A, Vita J. Cranberries and their bioactive constituents in human health. Adv Nutr. 2013;4:1–15.

- Liu H, Liu H, Wang W, Khoo C, Taylor J, Gu L. Cranberry phytochemicals inhibit glycation of human hemoglobin and serum albumin by scavenging reactive carbonyls. Food Funct. 2011;2:475–482.

- da Silva Pinto M, Ghaedian R, Shinde R, Shetty K. Potential of Cranberry Powder for Management of Hyperglycemia Using In Vitro Models. J Med Food. 2010;13(5):1036–1044.

- Shmuely H, Ofek I, Weiss EI, Rones Z, Houri-Haddad Y. Cranberry components for the therapy of infectious disease. Curr Opin Biotech. 2012;23:148–152.

- Gotteland M, Andrews M, Toledo M, Munoz L, Caceres P, Anziani A, Wittig E, Speisky H, Salazar G. Modulation of Helicobacter pylori colonization with cranberry juice and Lactobacillus johnsonii La1 in children. Nutrition. 2008;24(5):421-426.

- Zhang L, Ma J, Pan K, Go VL, Chen J, You WC. Efficacy of cranberry juice on Helicobacter pylori infection: a double-blind, randomized placebo-controlled trial. Helicobacter. 2005;10(2):139-45.